One of the common responses to my last few posts on trauma topics is the shock of well-meaning people when they learn the extent of harm caused in the church. Sometimes it looks like denial (the people whose response to hearing stories of harm is ‘that’s not how I remember it’), but for the most part, Christian leaders in my experience largely don’t intend to cause harm and aren’t ‘bad people’ per se; rather, they lack the frameworks to recognise systemic harm even when it’s starkly visible to others.

How is it possible for them to remain so unaware while such a long list of people are deeply affected by non-trauma-informed ministry approaches?

I believe a significant part of the answer is the phenomenon called ‘Survivorship Bias’ (or ‘Survivor Bias’). Survivorship Bias is a logical fallacy that occurs when a visible, successful subgroup is mistakenly assumed to represent the whole group because the ‘unsuccessful’ stories are not seen or considered. This leads to inaccurate perceptions about what ‘works’ for most people and compounds the harm already experienced by those who failed to survive the system.

Survivorship Bias is a logical fallacy that occurs when a visible, successful subgroup is mistakenly assumed to represent the whole group because the ‘unsuccessful’ stories are not seen or considered.

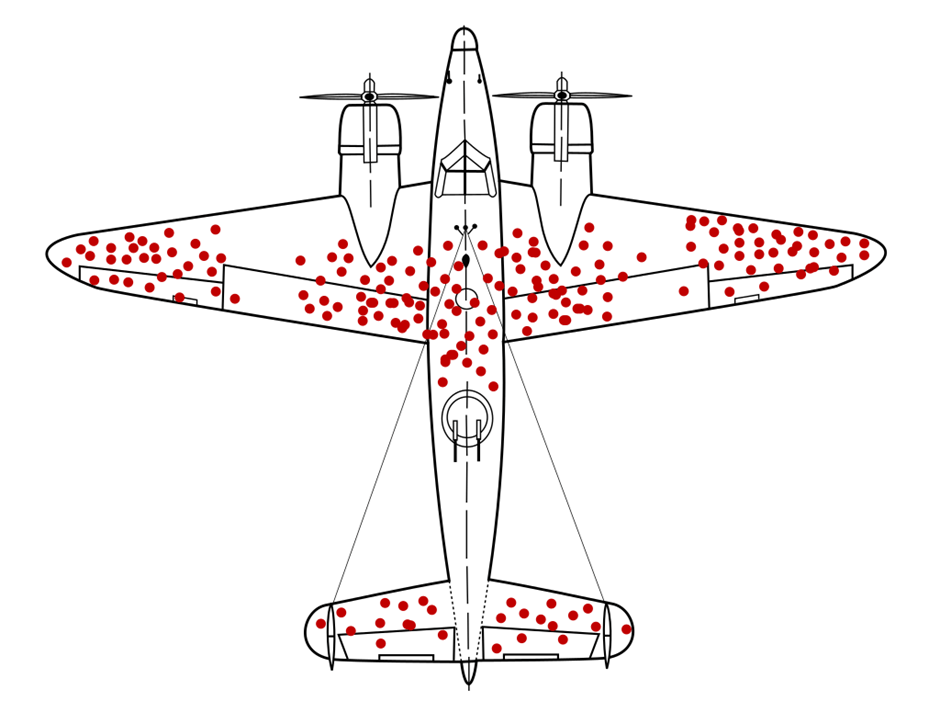

The classic example of survivorship bias is the famous story (whether myth or real) of statistician Abraham Wald who studied World War II aircraft in order to reinforce aircraft damaged in battle. As the story goes, Wald’s research team mapped out the areas most commonly damaged in planes returning from battle (image below).

While ‘common sense’ intuition would see these frequently hit areas as the most vulnerable areas and respond by reinforcing those parts of the aircraft, Wald allegedly argued that his team should take the exact opposite approach. He reasoned that these were the most frequently hit areas for the planes which actually returned, meaning they were, in fact, the least critical parts of the aircraft—these were the parts of the plane that could take a hit and still return safely home! These planes were the survivors. In contrast, the planes that got hit in other areas (like the cockpit or the engines which don’t have a single hit in this diagram!) were so critically damaged that they never returned and were therefore never even considered in the data set to start with. Wald reasoned that the underrepresented areas with no red spots were the most likely to be critical areas, so he focused his efforts on reinforcing those areas.

Whether the myth is true or not, the moral of the story is that if success stories are the only data you consider, you end up with a dangerously inaccurate picture of how well the system is operating. If we only learn from those who return or those who stay, we can only ever understand the perspectives of those the system allowed to survive. If we care about creating healthy and life-giving systems, though, the much more valuable data comes from those who did not survive the system—they are the ones who can illuminate the critical areas.

A conservative complementarian Bible college I know of held a consultation on women’s experiences at the college a while back. To their credit, I believe they had good intentions of hearing from women (a vastly under-represented demographic in that complementarian institution), and I sincerely believe that this desire to listen to and address women’s needs was the motivation behind the consultation process; I applaud them for this. But the problem with survivorship bias is that it distorts our perspective even when we seek to listen with the best of intentions. What happened was that specific women were selected and personally invited to participate in the consultation process. Can you guess what happens when participation is on an invite-only basis? A very particular subset of women are going to be invited: in this case, the kind of women who had been in the system long enough and were well-connected enough that the college leadership personally knew them and thought of their names to send them invitations.

I have no doubt that every one of these women invited to consult had incredibly valuable insights to share that the college benefited from; yet they are a non-representative sample consisting of specifically the type of women who survived the system, or even benefited from it, long enough that the college leadership knew them and respected them. What the college missed in this consultation process, though, was hearing from all the women that the system had failed. I know several women, including current students and alumnae of that college, who were deeply invested in conversations about women’s experiences in church leadership and had invaluable insights they would have loved to share, but who were simply never given the opportunity to enter the conversation.

My friend C was a current student who had pursued ongoing conversations about women’s experiences at this college, and she was not invited to the consultation. She’d heard general announcements that some kind of consultation was taking place but was never given the opportunity to offer her insights. She told me she thought that she’d been blacklisted for being too vocal about her complaints about women’s treatment there, and that she unsurprised no one approached her for her thoughts. Neither she nor I can say for sure whether she was intentionally passed over while her other women friends were personally invited, but either way, this was a woman deeply hurt by the system with some valuable insights for reform who was never given the opportunity to share them; whether by mistake or design, the outcome is the same.

This is one of the issues with power dynamics where the same group of people people call all the shots, decide which conversations we have when, and choose who gets to be in the room for those conversations. Even with the very best of intentions, these people will always have blind spots, and any attempts to invite people within their spheres of contact to share insights will remain inherently limited to those people who can survive being in their spheres of contact. All the people they may have [unintentionally!] harmed along the way who have left for different, safer spheres, are nowhere to be seen, and the most critical insights (using ‘critical’ in both senses of the word!) are lost.

If success stories are the only data you consider, you end up with a dangerously inaccurate picture of how well the system is operating.

I wrote about a similar phenomenon a while back when I argued that by telling only a very specific kind of success story (the ‘model minority myth’), even while it appears to be a celebration of that story, it can [unintentionally] isolate others who don’t fit into that vision of the “right” way to be a queer Christian (or Christian woman or trauma survivor, etc.) in the church).

In practice, this looks like having one token gay/SSA person in your Bible college/church/denominational leadership who reassures you that this is, in fact, a safe space—that he (and it is always a dude) has been met with nothing but acceptance and support in this space. I’m genuinely glad that this person experiences the system as a safe space, and I’m not here to tell them that they’re wrong… but the danger comes when we form a view of how safe everybody else is based on their experience, or form a view of how healthy our communities are based on that isolated perspective alone.

Forming views based on a biased data set set gives us an overly optimistic perspective – but optimism is not a virtue here. It’s an oversight that inaccurately leads to a presumption of safety that harms a huge list of people.

Forming views based on a biased data set set gives us an overly optimistic perspective – but optimism is not a virtue here. It’s an oversight that inaccurately leads to a presumption of safety that harms a huge list of people.

Responding to Survivorship Bias

What do we do with this, then?

1. Acknowledge your bias

There’s a certain inevitability in always having implicit biases, and that’s also true of survivorship bias; we delude ourselves if we think we can ever cure ourselves of these biases completely. Rather than relying on ourselves to develop infallible and totally unbiased perspectives, we should accept that we will always have blind spots and realistically acknowledge the limits of our own insights. This means, by extension, acknowledging the limits of our own reach and the target demographics we can meaningfully engage while relying on our own insights.

Accepting the inevitability of our own blind spots should also push us to surround ourselves with people who are different enough to us that they have different blind spots to us. Rather than presuming we can eliminate all bias from ourselves, we should work as different parts of the body, operating within a robust network of people with varied perspectives who are given actual power to effect change themselves based on those varying perspectives. This is why diversity of all kinds (including, but not limited to gender, sexual orientation, age, ethnicity, ability/neurotype, and class) at every level of church leadership is so important. If you’re a leader: never trust a system that relies on your own perspective to be infallible. You will remain biased, so plan to surround yourself with people (and systems!) whose biases lean in different, complementary directions than your own.

Practical suggestions:

- Employ female/queer/indigenous/POC/disabled/etc. people on your staff team and trust their perspectives when they differ to your own.

- When speaking on issues affecting LGBTQ+ people, invite an LGBTQ+ Christian to do the speaking (or a woman for issues affecting women, etc.). At the very least, if your system doesn’t allow those people to have a public voice (e.g. some complementarian theology), at least include them in your consultation process, and include them early enough to determine the direction you take before it’s set.

2. Actively seek out perspectives of those harmed by the system

The outworking of the above point is to not just stop at welcoming differing perspectives, but to go even further by identifying the people that your system has failed and reaching out to allow them to critique the system. It means seeking the people who left church, dropped out of Bible college or transferred, the people who visited your community but never came back, and the people who left the faith altogether.

For obvious reasons, we’ll need to be creative about how to realistically (and respectfully!) reach those who we’ve harmed. I’m still figuring out what this might look like (and would love your insights!) but I’ve got a few ideas:

- Find the people in your community who are already successfully bridging the gap with those marginalised people. Promote them to being the leaders in this endeavour, and follow their lead humbly.

- Always give people an out. If you’re asking advice from someone who’s been harmed by you[r system], recognise that you’re asking them to do free emotional labour which they are under no obligation to offer you. Make it easy for people to opt out unless they choose to engage. If they engage, acknowledge the power dynamic and make accommodations.

- Commit to understanding their stories on their terms. This means not just reinterpreting it through the lens of your own framework and appropriating it to serve your own purposes. A good way to check whether you’re appropriating someone’s insights is to ask yourself if the changes you actually make resemble that person’s own vision of change.

Practical suggestions:

Set up structures for providing critical feedback safely:

- Employ conference chaplains for attendees to debrief with confidentially and share any experiences of harm or trauma that come up at the conference. These conference chaplains would be people external to the power structures of the organisation who can collate feedback and anonymously share it back to the leaders without their own positions being threatened.

3. Look at the common traits of ‘success’ stories as indicators of harm, not health.

Even in situations where you’re not yet able to access data from people outside the system, you can still gain invaluable insights from the survivors’ success stories.

Remember how the plane diagram showed the ‘strong’ areas where not a single returning aircraft had taken a hit? By identifying the ‘unscathed’ areas of all the planes that returned the engineers were able to infer where the planes were most likely to be critically harmed; every aircraft that got hit in one of these areas never returned.

We can look at the qualities of all the people that survive or even thrive in our systems and identify the common traits as areas of privilege. The follow-up is to ask why people need to have these traits in order to survive our system. E.g. think of all the gay Christians you know of in your church. Are they mostly men? Or are they in mixed-orientation marriages with someone of the opposite gender? Are they all white?

Once you identify those common traits, you need to interrogate why the system disproportionately benefits those particular aspects and consider what can be done to make other experiences equally accommodated.

Practical suggestions:

- Review this list of people who are disproportionately harmed by non-trauma-informed churches and make a list of which demographics aren’t visible in your community. Try to identify patterns: what do the unrepresented demographics have in common? For those on the list who are visibly represented in your church, what is different about them? What do the stories of survivors teach you about how privilege works in your space, and how can you expand that privilege to benefit others on the margins?

One thought on “Survivorship Bias”